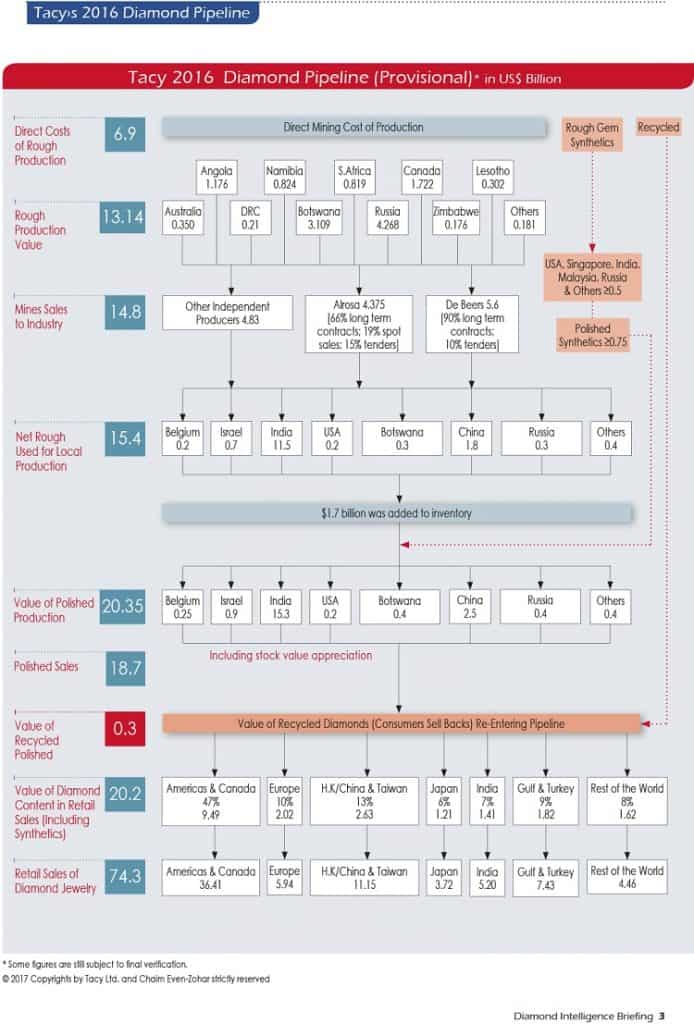

“Survival in the Absence of Growth” was the subject of a panel discussion at the recent Mumbai “Mines to Market Conference.” It certainly summarized succinctly the diamond industry’s 2016 performance. For five years in a row, the industry’s global polished diamond sales, measured in Polished Wholesale Prices (PWP), have followed a downward trend. Commencing in 2011, when sales peaked at $22.6 billion, this figure gradually declined to $18.7 billion in 2016 – registering a 17% accumulative decline. Last year, the decline was merely 3% over the $19.2 billion of 2015. Our economic models predict that in 2017, global polished sales will remain steady, while the industry’s rough replenishment will continue, comfortably absorbing the higher rough supplies already announced by the main producers.

A Glance at Each Pipeline Level

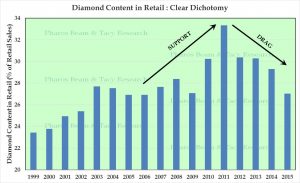

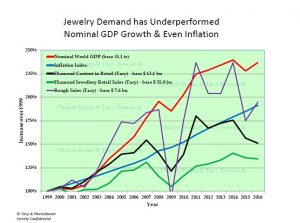

In 2016, diamond jewelry retail sales declined slightly by some 1.3% coming to $74.3 billion. This figure must be approached with caution, though: During the last five years, starting from 2011, the average diamond content in each jewelry piece declined. This trend still continues. In this respect, 2011 was an exceptionally good year – but generally speaking, the average diamond content (in PWP) historically represented some 25-28% of the jewelry piece’s retail value. This rose sharply in 2010-2013 to well over 30%. Since then, however, it has been sliding back to some 27%. [See graph] Thus, hypothetically, if in two years the same diamond retail value was sold globally, this does not necessarily mean that diamond contents would have been the same. They aren’t. At an average, there simply was “less diamond” in the overall jewelry piece – and gold, other precious materials or stones, design, etc. constitutes a larger part of the jewelry piece’s value.

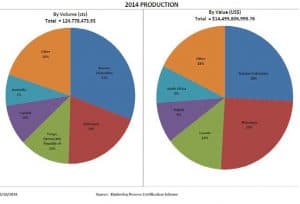

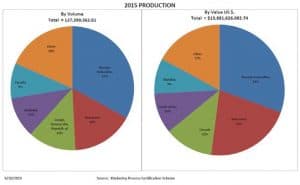

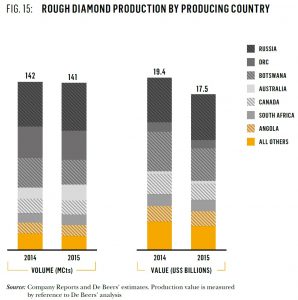

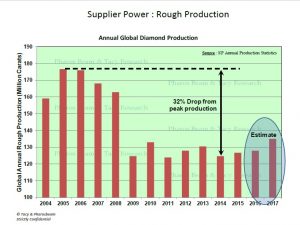

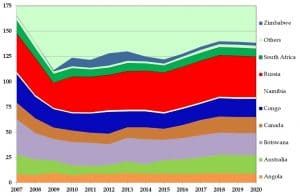

Diamond mining output almost returned to normal towards the final months of 2016, after it had fallen steeply in 2015. Both Alrosa and De Beers reduced output in 2016, as they were carrying excess rough stock which was not sold. Global diamond production totaled $13.4 billion in 2016, down from the $15.5 billion unearthed in 2015 – and still a far cry from the $16.5 billion produced in 2014. Over the last few years, producers were forced to stock surplus production (and Alrosa stepped up sales to the Gokhran state depository to avoid severe mining cutbacks), creating divergence in what was mined and what was sold to the market. Thus producer rough sales to the market, which peaked in 2014 at $18.0 billion and fell dramatically to $13.3 billion in the difficult year of 2015, slightly increased last year to $14.8 billion. In our forecasts, we expect that producers will sell well over $15 billion in 2017 – and they have already set higher mining targets.

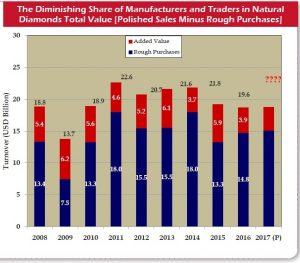

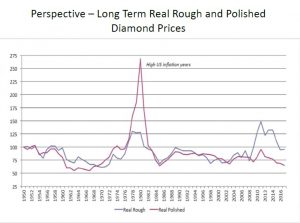

The restraint shown by the producers in 2015 and 2016 in the level of production, and the various reductions of rough prices, encouraged the midstream players in 2016 to replenish inventories; the lower price levels did not prevent the further widening of the mismatch between rough and the resultant polished prices. [See graph on page 9.] Our economic models, which analyze the diamond manufacturing and trading sector as if it were one “single midstream company,” show that the industry acquired rough for $14.8 billion and sold polished for $18.7 billion. Clearly, industry replenished and showed confidence by buying above current consumption levels. It also demonstrated optimism for 2017 – and a positive mood generally tends to drive greater purchases by both midstream and downstream (retail) sectors.

2016 Profitability: The Best Since 2011

Total midstream inventory levels rose by some $1.7 billion, from $10.6 billion to $12.3 billion in 2016. Historically, when viewing the ratio between midstream inventories and sales, the level of inventories have traditionally been higher. This shows that market price volatility is gradually reducing the appetite to maintain excess stocks – thus invalidating and putting to rest the “historic” belief that if one doesn’t make money in the business, one will make money on his inventories. Not anymore!

The mid-stream’s 2016 inventory growth was achieved while the industry slightly decreased its bank indebtedness, from $14.2 billion in 2015 down to $14.0 billion at the end of last year. While the overall financial health of the industry seems fine, there are some troubled (mega) companies that could receive adverse financial news at any moment – something that has been said about several companies for a long time.

What seems significant is that the bottom line in the midstream’s businesses profit and loss accounts slightly rose. However, many companies also faced inventory value write downs, largely (or at times completely) wiping out the gains recorded. This is a consequence of the price volatility at the producer’s level.

In a presentation to investors in January 2017, Russia’s Alrosa diamond mining conglomerate observed that in 2015 the margins of the diamond cutting and polishing segment of the pipeline “was less than 1%.” We agree. Our figures confirm that in 2016, it rose slightly – and we hope that Alrosa’s findings will state likewise. As we said: Profit-wise, 2016 was the best year since 2011.

In each and every diamond center, the players report that there is ample liquidity. At the recent Mines to Market conference in Mumbai, each and every main banker confirmed that their diamond clients are well below the maximum utilization of their credit lines. The diamond miners, which have announced their plans to increase their production and sales to the market in 2017, should meet no serious problems – as the industry still has a comfortable absorptive capacity.

Fake News and Alternative Facts

Tacy Ltd. has published its annual pipeline since 1988 – this current version is our 28th in a row. For most of these years, there were minor divergences between our figures and those presented by De Beers, other mining companies, and economic research organizations, regarding estimations of mining output and rough sales to the market. Beginning in 2012, we saw that the data published by De Beers (through its authoritative Insight Reports) showed material differences with our data – both in terms of mine production and rough supplies to the market, therefore also of the resultant polished sales. The figures from De Beers seem unreasonably inflated and are inconsistent with the financial reporting of producers.

Why is this a concern? The global diamond production figures by De Beers are annually some $4.7-$5 billion higher than the annual reports of the Kimberley Process (KP) and the consensus views by those other organizations which don’t simply cut and paste the De Beers figures as the gospel truth.

Admittedly, these rough production figures are not an exact science, but if De Beers claims that global production, measured in value, is 30-40% more than what the KP has recorded, this inevitably raises troubling questions. One quite controversial “State of the Industry” presentation at the Mines to Market conference suggested that if De Beers claims that there is $5 billion worth of rough more out there that evidently escapes KP monitoring, then that must be black money or theft from African countries that “you guys” (meaning the industry) somehow must be holding and hiding, thundered the speaker. He added that if it wasn’t $5 billion, but only $1 billion, that would still be equally serious in terms of what terrorists and money launderers could do with that money.

It’s not just the values, it’s also the volumes. The bigger concern on the rough-production-values front is the mismatch of carat numbers. De Beers’ numbers show carat production at nearly 15 million carats higher than KP numbers. While value differences can be debated to a slight degree, carat differences imply that the KP is simply deficient. For the sake of the industry, we hope that De Beers takes a strong look at their numbers.

Explaining Data Discrepancies… Or Not

Tacy Ltd. publishes its pipeline figures every year many months before the KP production figures are collected and published. Our estimate for 2016 is $13.14 billion, at rough production values. By value this represents a decline of some 15% below our $15.5 billion figure for 2015. But one shouldn’t forget that the producers’ policies of “artificially” reducing output to produce in line with demand that was announced in the latter part of 2015, and this reduction in prices, show its impact in all severity in 2016. Our figures are generally slightly above the KP, as we base our data on production per mine – though we do realize that there are a few (mostly two) producer countries where export values are intentionally understated by the respective governmental authorities for reasons best known to them.

In the past few years, several analysts have alerted De Beers to the discrepancies (as we also did), but no corrections have been forthcoming. It’s a smart company; it will have its reasons. The overstated mining figures by De Beers also enable it to overstate industry sales, and thus project an image of continuous industry growth – even when this growth is elusive. By significantly overstating total production, it reduces its own dominant size in the market – which may stem from competition policy considerations. It is hoped that De Beers will either review or substantiate its figures.

Synthetics Has Become a Zero-Sum Game

What characterizes 2016 more than anything else is the aggressive behavior of the gem-quality synthetics (lab-grown) producers. The polished diamond output of the dominant synthetic (lab-grown) rough producer, which manufactures and sells the polished itself or through subcontracting, enters the consumer market largely undisclosed – especially through set-jewelry, where the chances of “discovery” are near zero. In value, we estimate that some $750 million of gem synthetics (lab grown) were sold in 2016. [Our $750 million represents the natural PWP equivalent, as they effectively eat into the demand for natural polished. The production and sale cost for the same can be significantly lower.] In terms of volumes, especially melees, the amounts of undisclosed synthetics in the markets are staggering.

Anglo American Corporation, which owns 85% of De Beers, has, for the first time ever, categorized the growing market of synthetic gem-quality diamonds as a “principal strategic risk” to the company. This status propels a mandatory ongoing “risk management” monitoring and (mitigating) action process. In such a process, the company must continuously decide whether actions are effective and whether the risk “falls inside or outside the limits of our risk appetite.”

The company has now unequivocally stated that “demand for (natural) diamonds reduces as a result of developments in the synthetic industry.” While we have argued that point for several years already, the producers hitherto envisioned that availability of “detection equipment” would lead to the development of two distinct markets – synthetic (lab-grown) and natural diamonds. Theoretically, that would be a win-win situation, prospering in a price-wise and product-wise two-tiered market. However, this is wishful thinking.

Basically, Anglo American implies that synthetic (lab-grown) diamonds are considered an economic substitution for natural. An engagement ring sold with a synthetic diamond means the loss of a sale with a natural diamond. But it goes beyond that. Anglo-American is concerned about synthetic marketing and product positioning.

Anglo American Corporation now acknowledges in its 2016 Annual Report that “technological progresses are making the production of man-made gem synthetics commercially viable and there are increased distribution sources.” It goes a step further. It realizes that “the marketing of synthetics seeks to place them as being environmentally or socially superior.” [Please read that line again: “The marketing of synthetics seeks to place them as being environmentally or socially superior.”]

This is the real strategic threat: Huge financial resources are poured in by the synthetic producers to delegitimize natural diamonds – to convince consumers that “natural diamonds” are bad or even evil. Synthetics are simply positioned, as Anglo said, as “environmentally and socially superior.”

The impact on De Beers is a “potential loss of polished and rough diamond sales leading to a negative impact on [the producer’s] revenue, cash flow, profitability and value,” states Anglo American. The risk-mitigation strategy is mainly to position synthetics as a “different” product and the development of detection technologies.

We assume that if the point is ever reached that the risks fall “outside the limits of risk appetite,” Anglo American would most likely dispose of its diamond mining assets. They haven’t reached that point yet – it’s never even mentioned – but declaring synthetics as a “principal risk” would be the first step in such a decision-making process.

Diamond Midstream’s Ambiguous Position on Synthetics

Diamond manufacturers tend to bend over backwards to curry favor with natural producers. That’s the result of almost a century of the De Beers sightholder system: A manufacturer or rough trader is dependent on the goodwill and willingness of the producer to sell the rough to you rather than to someone else. Diamond manufacturers’ revenues – and margins – depend on the added value created between purchase of raw material and sales of resultant polished.

The rise of synthetics has decreased the hold, the “grip” if you want, of the natural producers over their clients. A manufacturer in Surat (or anywhere else for that matter) wants to optimize his added value and margins. If there is more money to be made by cutting and polishing synthetics, he sees no reason why he shouldn’t do so. Anglo American didn’t state it so bluntly, but the reduced demand that for natural diamonds it signals isn’t just coming from consumers, but rather also from the midstream sector.

During the Mines to Market conference, several speakers outdid each other in vehemently and loudly declaring that “synthetics are not diamonds.” Some of the world’s largest synthetic diamond manufacturers (not producers) were in the room, as were some of the distributors. For [valid] commercial reasons, they don’t want to publicly identify themselves – as, inevitably, some of them may also directly or indirectly be clients of De Beers, Alrosa and other natural producers. One manufacturer [of small synthetics] confided that “even if costs would be equal, some of the synthetics simply look better in the jewelry piece.”

One of the mainstream’s most influential leaders warned me this week not to “target” companies that widely sell synthetics, but only those who strongly delegitimize the natural diamond business. In today’s reality, it is difficult to distinguish the dividing line. One might ask whether it matters if one product is positioned and marketed as “superior” to the other, as long as the person that carries both business lines is doing each of them legitimately.

The fact that some major industry leaders in Europe and America have prospering synthetic businesses complicates the issue. Synthetics have become widely accepted by the midstream – especially as there are better margins to be earned since synthetic rough production prices have been going down in the last two years. Synthetic rough needs to be polished; especially the small goods, which are labor intensive. They supply welcome employment. We are not aware of any credible reports on “resistance to synthetics in the consumer markets,” in spite of natural producers telling us at every opportunity that a woman only wants the “real” thing.

It’s the Bottom Line that Will Drive the Choices

Ultimately, it all comes down to a question of bottom line. In a scenario of low profitability, it is not wrong for well-run businesses to consider diversification into other allied businesses, including synthetics. The only ones who have no option are the rough producer countries and rough producing companies. Hence, it will be in their long-run interest for rough producers ensure that the midstream industry continues to remain profitable.

Anglo American may not realize yet how serious the principal risk is that it has identified. Its situation is, in a way, better than those of other producers: Anglo American, through its Element 6 synthetics subsidiary, has the choice to “join the lab-grown business.” Many are convinced that this will eventually happen – and it’s more a question of “when.” Undoubtedly, they have the state-of-the-art technology and the patents to enable a swift market entry.

Lab-Grown Producers Lobby FTC

In 2016, the main producer of gem-quality synthetics re-established the International Grown Diamonds Association (IGDA) to lobby the U.S. government. In a submission to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), it cited research showing “that in 2014, laboratory-grown diamond production was approximately 360,000 carats. By 2018, global laboratory-grown gem-quality diamond production globally is estimated to reach close to 2 million carats and by 2026 it is expected to cross 20 million carats.

In our Pipeline Chart, we estimate polished synthetic sales at 4% of overall polished diamond sales. Incidentally, the FTC is asked by the IGDA to amend its Jewelry Guides regarding marketing nomenclatures and to “prohibit the use of the term ‘synthetic’ to describe laboratory-grown diamonds, as this term is misleading, deceptive, and confusing to consumers,” it says.

“The properties of these laboratory-grown diamonds have been found to be optically, physically, and chemically identical to the earth-derived diamonds. The only difference between laboratory-grown diamonds and mined diamonds is their point of origin. Moreover, many of the human and environmental impacts associated with mining diamonds from the Earth are significantly lessened, and in some instances entirely removed, with laboratory-grown diamonds.” This implicitly underscores what Anglo American observed: Synthetic (lab-grown) diamonds are in many cases promoted as being socially and environmentally superior over natural.

Our main concern is that the lion’s share of the synthetic production is not clearly disclosed throughout the value chain. It’s fraudulent – though experts expect that in due time the differences will dissipate.

Synthetics’ Impact on Rough Prices and Diamond Exploration

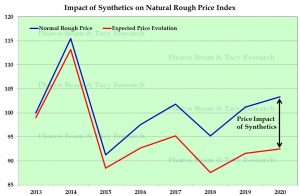

Anglo American correctly noted the impact of synthetics on natural producers’ rough selling prices. In the supply curve analysis of rough diamond prices conducted by Pharos Beam Consulting and Tacy Ltd, it seems that current rough prices are some 4% below the “normalized prices,” i.e., the price level the rough prices would have reached if there were no synthetics in the market. [The supply curve is a graphical representation of the relationship between the price of a good or service and the quantity supplied for a given period of time.] We expect this gap to grow to 10% by 2020 [see chart].

The competition provided by synthetics will eventually have a distinct effect on producer and producer countries’ policies. It discourages exploration companies to devote resources to search for new diamond deposits. It may take years to find a deposit, if at all, and to assess economic feasibility. By the time an economically viable deposit has been confirmed, it may take a few more years (and hundreds of millions of dollars) to develop a mine. At the same time, mass production of synthetics – and the public’s acceptance of these man-made stones as an economic substitute for natural diamonds – may make the new mine unviable from the start.

At De Beers, for example, its 2016 exploration budget was 15% lower than it was in the previous year – down from $34 million to $29 million. It must be noted, however, that this represented a general trend of reductions across all commodities. Having said that, $34 million represents the equivalent of 0.2% of annual production. That hardly seems like an investment in the search of future deposits.

Though De Beers and Alrosa operate on comfortable profit margins, there are nevertheless among the global diamond producers several operating mines that have been put on “care and maintenance” – a euphemism for a situation where the costs of production exceed the value of the output. If the rough price doesn’t rise sufficiently, these assets will eventually be disposed of or shut down. Analysts fear that Australia’s Argyle mine could shortly join that list, which would reduce global rough diamond supply by some 27-20 million carats (valued around $420 million) of predominantly small (though labor-intensive) diamonds.

The producers are deeply concerned about losing consumer confidence in diamonds. But what about the governments of mining nations? A research paper by a Botswana public policy think tank has suggested that leaving diamonds in the ground, assuming that they eventually (when mined) would yield a higher price, may well be a faulty assumption. And diamonds in the ground don’t produce current income – no annual yield. This is clearly not a popular view.

Price Volatility and Risks – Concern for Entire Pipeline

The Tacy Pipeline provides simple numbers. Behind each figure hides amazing stories – and ever-changing realities. The ciphers speak for themselves – and in this review only some salient issues were discussed. If one had to identify a single overriding concern shared by all players, it would be the enormous price volatility. This is quite a recent phenomenon in an industry in which (artificially maintained) price stability was probably one of its greatest attractions – providing comfort to all stakeholders, especially governments and bankers.

The midstream players don’t like auctions. At every conference, emphasis is placed on the desirability of long-term contracts, and our pipeline made a point in the “mine sales” category to identify the marketing mechanisms of the two main rough suppliers. Miners warn that the current geopolitical and macro-economic uncertainties are expected to cause continued price volatility – not only in diamonds, but in most other commodities as well. Overall, the commodity pricing environment seems to be increasingly more spot-price based, compared to the mid- or long-term contract-pricing mechanisms that used to be the norm.

At the Mines to Market conference, there was one speaker offering a commodity trading platform enabling diamonds packaged in standardized packages to be traded by outside investors. A non-physical diamond trading activity where papers will exchange hands. In the past, these diamond commodity ventures, trading diamond-backed papers rather than diamonds, have always been short-lived and have generally only provided some profits to their promotors. Whether it will be different this time, we wouldn’t know.

The mining companies are acutely aware of the impact of price volatility. They feel constraint, and it generally reduces their “appetite” for investments in new mining projects. Whether two new Canadian diamond mines will actually be put into production depends on market prices – which are unpredictable now. Mines know their risks. The midstream may be less aware – or has seldom quantified its own risks.

In our 2016 Diamond Pipeline, we stressed the good news – that money was made in 2016. It also highlighted that synthetics have become an integral part of the diamond value chain and that more decisive action is needed, also to avoid a withdrawal of explorers and natural miners from the market. Natural producers must also understand that their most “effective” fight against synthetics comes from a healthy midstream. It’s the bottom line that counts. If the industry’s midstream players would set fair earning targets, and the producers would allow them to secure a decent return-on-capital based on the present macro-economic risk profiles, we wonder how different the sharing of the considerable added value in the annual pipeline would look. A shift in favor of midstream can do wonders! Let’s wait for 2017 – but don’t hold your breath.

Diamond Jewelry is Losing its Share of the Luxury Wallet – Forever?

The diamond jewelry market is losing its share of the consumer’s luxury wallet. The growth of diamond jewelry retail sales lags dramatically behind (nominal) global GDP growth. Diamond jewelry retail sales, since 2007, have fallen steeply behind inflation indices. In our 17-year pipeline chart [above], using an index (base) of 100 for the year 1999, diamond jewelry retail sales have risen by merely some 130%, while GDP rose by 240%. The diamond content in jewelry had risen to some 180% by 2011, but has fallen back to 150%. The diamond jewelry market is underperforming almost any relevant economic parameter.

However, are we doing worse than other luxury items? Bain & Co. recently published its authoritative 2016 LUXURY GOODS WORLDWIDE MARKET STUDY. “The overall luxury industry tracked by Bain & Company comprises 10 segments, led by luxury cars, luxury hospitality and personal luxury goods, which together account for approximately 80% of the total market. The overall [luxury] industry has posted steady growth of 4%, to an estimated €1.08 trillion in retail sales value in 2016. Yet among specific categories, there was a clear spread in this past year’s performance,” says Bain & Co.

“The market for personal luxury goods—the “core of the core”—was essentially flat, at €249 billion. That represents a 1% contraction at current exchange rates and no change in market size from €251 billion in 2015 (at constant exchange rates). This is the third consecutive year of modest growth at constant exchange rates, and it represents a new normal in which luxury companies no longer benefit from a favorable market and free-spending consumers. Brexit, the US presidential election and terrorism have all led to significant uncertainty and lower consumer confidence, hindering sales of personal luxury goods.”

“The Americas and Asia (excluding Japan) —two major luxury markets—both contracted by 3% in 2016. Europe declined 1%, primarily due to a decline in tourism, and potentially would have performed worse were it not for strong sales in the UK (driven by a depreciated British pound). In China, consumers started buying again in their home market, but that was not enough to offset a dip in purchases by Chinese travelers abroad. A key factor in this shift is tighter customs controls to limit foreign shopping in an effort to fight the “grey market” of unauthorized sales and stimulate domestic consumption. As a result, China’s overall share of global luxury goods purchases declined slightly from 31% to 30%,” concludes the consulting company.

The diamond jewelry business is basically in the same boat as the “core luxury business”. “Luxury cars, luxury travel (cruises), fine restaurants, fine wines and spirits, and fine food segments all grew, reflecting a redirection of luxury spending away from goods and toward personal pampering and experiences.”

Our pipeline gives global GDP growth. The producers, in their rough diamond sales, have steadily outperformed global GDP in the 2000-2007 period – and grown in tandem in a volatile manner. Though bouncing back up there in 2011, it has not kept pace with GDP since then – and has fallen in recent years, though rising lately. The producers have a great price-setting capacity, strongly based on their oligopolistic roots. The luxury markets are extremely competitive – and there diamonds are losing out. The midstream, as its name implies, is somewhere squeezed in between.

Article written by Chaim Even-Zohar and published in Tacy’s Annual Diamond 2016 Pipeline Issue, Vol. 33, March 26, 2017